Artists can now opt out of generative AI. It’s not enough.

Opting out is the latest example of generative AI developers externalizing costs.

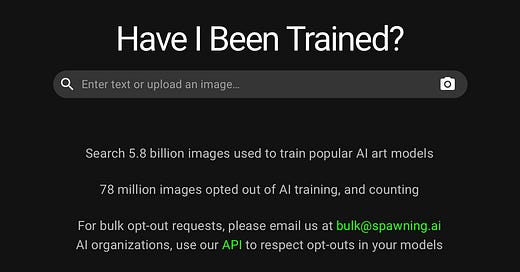

Text-to-image models like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E are trained on vast amounts of data collected online—including images created by artists, without their consent. In response, artists developed the website Have I been trained, which allows any artist to check whether their art was used to train Stable Diffusion. It also allows artists to individually mark their images as "opted-out" of training data for generative AI.

Stability AI said that it would honor opt-out requests made using this tool. Over 80 million artworks have been opted out in the last few months. But will this help artists?

Opt-outs are an ineffective governance mechanism

Giving artists the choice to opt out seems compelling. But it is unlikely to be effective on its own. The law does not bind developers of generative AI tools to respect opt-outs. (UPDATE: The creators of Have I Been Trained point out that the EU’s 2019 copyright directive prohibits companies from training ML models using opted-out content. This suggests that companies might be legally required to respect artists’ opt-out choices, at least in Europe.) None of the other major players—OpenAI, Google, and Midjourney—offer artists the choice of opting out.

Many artists are unaware that their art is used to train AI models. On top of that, the process for opting out is time-consuming, opaque, and unintuitive. It requires artists to upload their images one at a time and opt the resulting images out individually.1

Considering all this, the number of images opted out is likely a small fraction of what it would have been if developers needed to notify artists and get their consent. While 80 million images seems like a big number, Stable Diffusion is trained on a dataset containing over 2.3 billion images.

Art communities such as ArtStation and DeviantArt have implemented their own version of opting out. But art from these communities is often copied to other forums without the artists' knowledge. It becomes hard to track down each copy of their art.

The (time) cost of opting out is pushed onto artists

The onus for opting an image out of training data rests on the artist, resulting in unpaid labor. For one artist, it is a headache. For the millions of artists who might want to opt out, this is a massive time cost.

Let's say artists wanted to opt out a hundred million images from the training data of generative AI tools (about 5% of training data).2 If each image opt-out takes a minute—a conservative estimate, since opting out requires uploading each individual image, going through the search results, and selecting all matches—and artists' time is valued at USD 15 / hour, this process costs USD 25 million.

This is about a quarter of the entire funding that Stability AI has raised so far—just for respecting opt-outs from a fraction of the artists. The costs of actually licensing artwork to include it in text-to-image models would likely be astronomical in comparison.

Of the 80 million images opted out, only about 40,000 came from individual artists. That’s less than 1 in 2,000. The rest were opted out in bulk by platforms such as Shutterstock and Artstation. This shows that even the small dent made by opting out was only possible because of collectives looking out for artists. That’s the crux of the issue: the problems that generative AI creates are structural and collective. They cannot be solved by pushing the responsibility to individuals.

Generative AI companies routinely externalize costs

Appropriating the labor of artists is just one example of generative AI companies pushing the costs of running their business onto third parties.

ChatGPT relied on human feedback to reduce the toxicity of outputs. OpenAI outsourced this feedback to contract workers in Kenya. An investigation into the company found it was paying workers in Kenya less than USD 2/hr while asking them to classify toxic content, including graphic descriptions of child sexual abuse and self-harm.

When ChatGPT was released, educators struggled to adapt—teachers who assigned essays would have to create new assignments. We've written about why this could be healthy for education in the long run, but the short-term consequences will be borne entirely by already underfunded teachers.

And when Microsoft released the chatbot-powered Bing, the company pushed the cost of testing it for harmful outputs partly onto third parties. Early adopters and journalists found many examples of the bot’s tendency to produce wildly inappropriate outputs. In response, CTO Kevin Scott made the implausible claim that it was impossible to discover these problems through internal testing.

It's clear that if generative AI companies want to do right by artists, their current business model is impractical. Creating opt-outs and other stop-gap interventions will only go so far, since they do nothing to change companies' business models or challenge prevailing labor conditions.

There is an urgent need for structural change. Here, too, artists are leading the way by pushing for legislation and filing class-action lawsuits to defend their rights and livelihood.

We are grateful to Mona Wang for her valuable input to this post.

Further reading:

Artist Steven Zapata argues against opt-out provisions for generative AI and outlines a different model that is more respectful to artists in this Youtube video.

In The Exploited Labor Behind Artificial Intelligence, Adrienne Willams and others highlight that concerns about AI doomsday scenarios hide the real-world harm already occurring due to AI tools. They outline worker organizing and unionization as key interventions for improving the living conditions of workers behind AI tools.

In their book Ghost work, Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri show the invisible labor that drives tech companies and is used for everything from content moderation on social media to verifying your Uber driver's identity.

The tool was made by artists who wanted to help other artists. We do not blame them for these issues. Instead, the blame lies with the developers of generative AI tools. Developers profit off their tools but don't build the key infrastructure required to make generative AI tools sustainable.

The online art community DeviantArt alone hosts over 370 million unique artworks.

Even "off the shelf" generative AI models that fully respect an artist's right to opt out can still be fine-tuned using a specific collection of images to deliberately imitate someone's style. I certainly support regulating these companies to make sure they respect artists' rights, but it is much more difficult to think of a solution to the problem of someone tuning a model locally on commodity hardware. Right now it takes a bit of technical knowledge, but I'm sure a consumer-grade app that can be run locally will have fine-tuning capabilities soon.

https://waxy.org/2022/11/invasive-diffusion-how-one-unwilling-illustrator-found-herself-turned-into-an-ai-model/

This is yet another example of the big grift promulgated by the originators of Web/Internet 1.0. To solve this problem we need to go back and understand the root cause is lack of settlements which provide incentives and disincentives and distribute wealth equitably for sustainable and generative networked ecosystems. The principles around efficient settlement systems apply to all of humanity's networks; but are easily implemented for digital networked ecosystems. More here: http://bit.ly/2iLAHlG