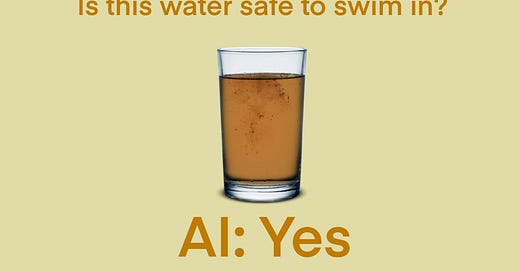

Toronto recently used an AI tool to predict when a public beach will be safe. It went horribly awry.

The developer claimed the tool achieved over 90% accuracy in predicting when beaches would be safe to swim in. But the tool did much worse: on a majority of the days when the water was in fact unsafe, beaches remained open based on the tool’s assessments. It was less accurate than the previous method of simply testing the water for bacteria each day.

We do not find this surprising. In fact, we consider this to be the default state of affairs when an AI risk prediction tool is deployed.

The Toronto tool involved an elementary performance evaluation failure—city officials never checked the performance of the deployed model over the summer—but much more subtle failures are possible. Perhaps the model is generally accurate but occasionally misses even extremely high bacteria levels. Or it works well on most beaches but totally fails on one particular beach. It's not realistic to expect non-experts to be able to comprehensively evaluate a model. Unless the customer of an AI risk prediction tool has internal experts, they’re buying the tool on faith. And if they do have their own experts, it’s usually easier to build the tool in-house!

When officials were questioned about the tool's efficacy, they deflected the questions by saying that the tool was never used on its own—a human always made the final decision. But they did not answer questions about how often the human decision-makers overrode the tool's recommendation.

This is also a familiar pattern. AI vendors often use a bait-and-switch when it comes to human oversight. Vendors sell these tools based on the promise of full automation and elimination of jobs, but when concerns are raised about bias, catastrophic failure, or other well-known limitations of AI, they retreat to the fine print which says that the tool shouldn't be used on its own. Their promises lead to over-automation—AI tools are used for tasks far beyond their capabilities.

Here are three other stories of similar failures of risk prediction models.

Epic’s sepsis prediction debacle

Epic is a large healthcare software company. It stores health data for over 300 million patients. In 2017, Epic released a sepsis prediction model. Over the next few years, it was deployed in hundreds of hospitals across the U.S. However, a 2021 study from researchers at the University of Michigan found that Epic’s model vastly underperformed compared to the developer’s claims.

The tool's inputs included information about whether a patient was given antibiotics. But if a patient is given antibiotics, they have already been diagnosed with sepsis—making the tool’s prediction useless. These cases were still counted as successes when the developer evaluated the tool, leading to exaggerated claims about how well it performed. This is an example of data leakage, a common error in building AI tools.

In a 2021 response, Epic tried to deflect criticism by claiming that their AI tools are not used on their own: "The robust clinical workflows and processes that surround these tools are what give the tools purpose and allow for improved outcomes". But the opposite was true: 88% of the tool’s alerts were false alarms, further increasing the workload on healthcare workers. A year later, Epic stopped selling its one-size-fits-all sepsis prediction model.

Dutch childcare benefits scandal

In 2013, the Netherlands deployed an algorithm to detect welfare fraud by people receiving childcare benefits. The algorithm found statistical correlations in the data, but these correlations were used to make serious accusations of guilt—without any other evidence.

The algorithm was used to wrongly accuse 30,000 parents. It sent many into financial and mental ruin. People accused by the algorithm were often asked to pay back hundreds of thousands of euros. In many cases, the accusation resulted from incorrect data about people—but they had no way to find out.

Shockingly, one of the inputs to the algorithm was whether someone had dual nationality; simply having a Turkish, Moroccan, or Eastern European nationality would make a person more likely to be flagged as a fraudster.

Worse, those accused had no recourse. Before the algorithm was developed, each case used to be reviewed by humans. After its deployment, no human was in the loop to override the algorithm’s flawed decisions.

Despite these issues, the algorithm was used for over 6 years.

In the fallout over the algorithm’s use, the Prime Minister and his entire cabinet resigned. Tax authorities that deployed the algorithm had to pay a EUR 3.7 million fine for the lapses that occurred during the model’s creation. This was the largest such fine imposed in the country.

This serves as a cautionary example of over-automation: an untested algorithm was deployed without any oversight and caused massive financial and emotional harm to people for 6 years before it was disbanded.

Family separation in Allegheny county

In 2016, Allegheny county in Pennsylvania adopted the Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST) to predict which children are at risk of maltreatment. AFST is used to decide which families should be investigated by social workers. In these investigations, social workers can forcibly remove children from their families and place them in foster care, even if there are no allegations of abuse—only poverty-based neglect.

Two years later, it was discovered that AFST suffered from data leakage, leading to exaggerated claims about its performance. In addition, the tool was systematically biased against Black families. When questioned, the creators trotted out the familiar defense that the final decision is always made by a human decision-maker.

There are many other examples of AI being particularly ill-suited for risk prediction; in an upcoming paper, we look at 8 consequential examples and find that they are all prone to failure in similar ways. Without scrutiny, all such tools are suspect.

Of course, when companies are asked to share their models for scrutiny, they throw their hands up with cries of "trade secret"—this happened with Epic, Northpointe (the company that makes the infamous recidivism prediction tool, COMPAS), and many other firms that sell such tools.

The takeaway is clear: the onus should be on the company selling the AI tool to proactively justify its validity. Without such evidence, we should treat any risk assessment tool as suspect. And that includes most tools on the market today.

Further reading

History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme. In Michigan, an algorithm was used to detect unemployment fraud from 2013-2015. The state incorrectly collected USD 21 million from residents. In another fraud detection scandal, the Australian government stole AUD 721 million from its citizens from 2016-2020. Citizens were accused of welfare fraud using an algorithm; this is often called the “robodebt” scandal.

J. Khadijah Abdurahman offers an incisive and gut-wrenching take on family separation and the role of AI tools—including AFST—in amplifying its harms.

In her book Automating Inequality, Virginia Eubanks dives into AFST and how it penalizes poverty. An excerpt of the chapter on AFST was published in WIRED.

Madeleine Clare Elish and Elizabeth Anne Watkins study another sepsis prediction algorithm—Sepsis Watch—that was deployed at Duke University. They document the painstaking work needed by clinicians to incorporate the model into their hospital-specific workflows and social context. This was aided by the fact that the tool was developed in-house, in contrast to the usual portrayal of AI tools as plug-and-play.

Elish also develops the concept of moral crumple zones: blaming incorrect decisions taken using automated systems on human operators without asking if they can provide reasonable oversight.

Ben Green argues that human oversight is overrated: it legitimizes faulty tools, provides a false sense of security, and cannot address the fundamental issues with algorithms.

Deb Raji et al. offer a taxonomy of the different kinds of failures that have occurred in real-world AI systems beyond risk prediction.

The ideas in this post were developed during a research project with Angelina Wang and Solon Barocas. Link to cover image source.

You guys are the designated drivers in the AI hypeway .. Thank you for being the sober ones.

Thanks for highlighting this. It's such an important topic. One of the root sources of overoptimism of ML performance is the academic literature. We documented this for digital health:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-021-00521-5

and talked about implications here:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ai-in-medicine-is-overhyped/